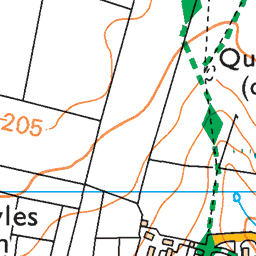

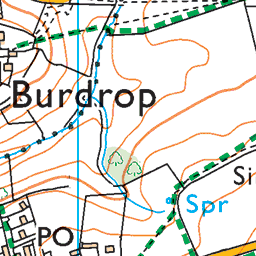

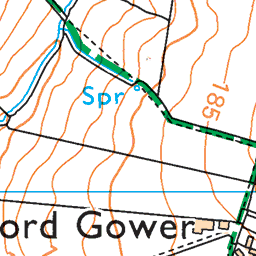

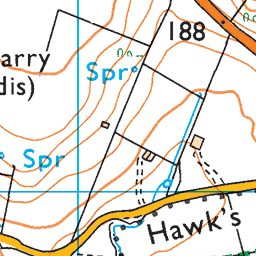

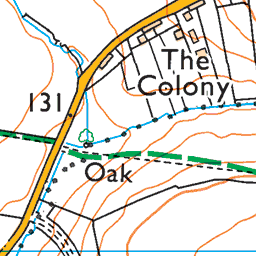

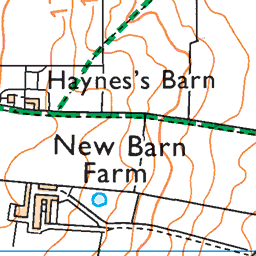

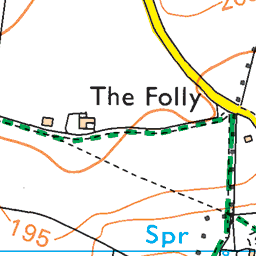

Village industries c.1865

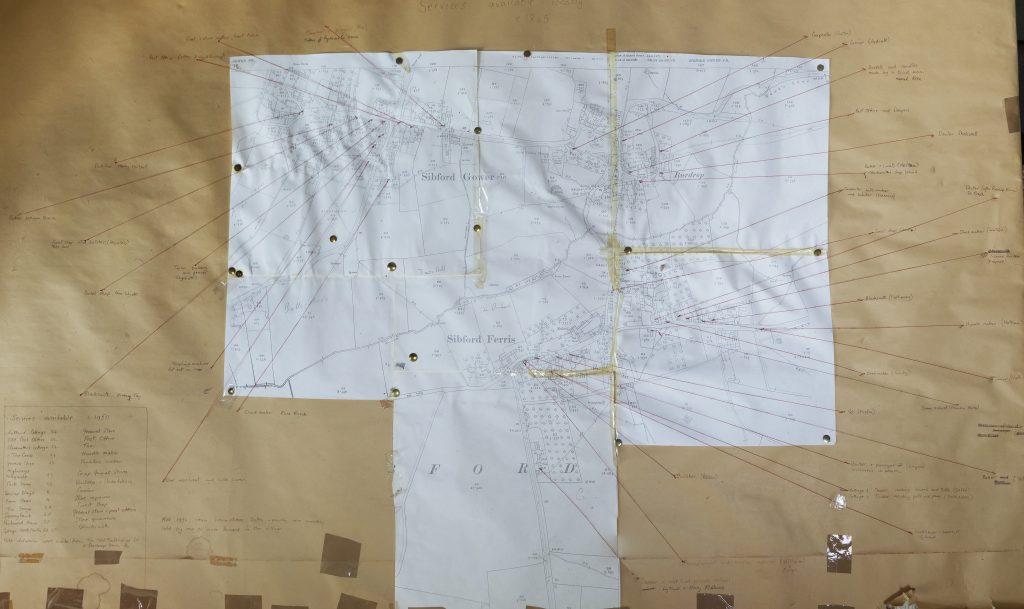

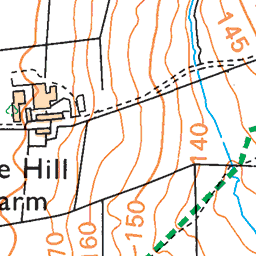

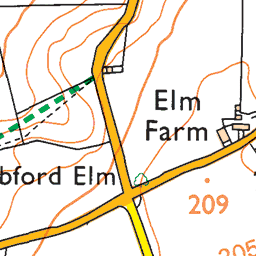

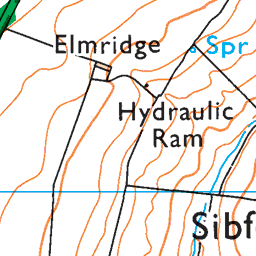

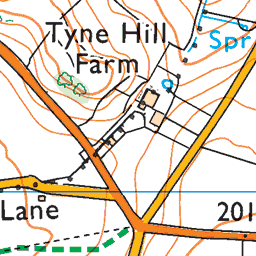

The map diagram above was created by Arnold Lamb (1929 – 2017) to illustrate a talk to The Sibfords History Society. It shows the locations of numerous village industries in the 1860s.

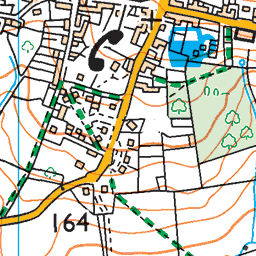

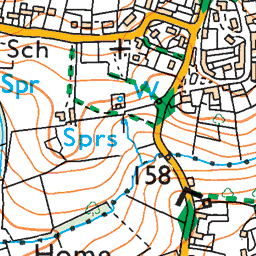

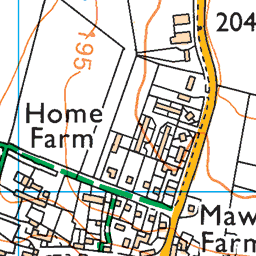

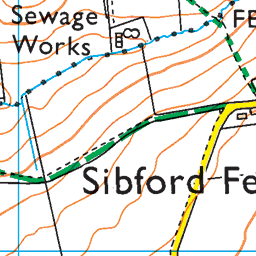

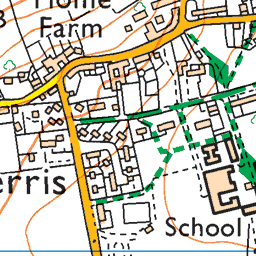

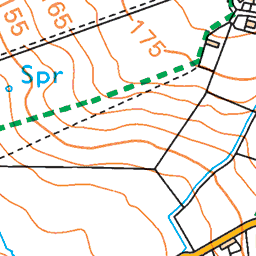

The same locations are shown on the modern OS map below. Click / touch a marker to pop-up its label; alternatively, click / touch one of the industries listed below the map to fly to its location on the map.

- Baker (Holtom) F

- Baker (William Brown) G

- Baker and sweets (Holtom)

Blacksmith's shop behind G - Barber (Haynes) F

- Baskets and candles made by blind man (Keen) G

- Beerhouse (Prophett) F

- Blacksmith (Hathaway) F

- Blacksmith (James Tay) G

- Bookkeeper F

- Boot and shoe maker (Robert Austin) G

- Butcher (Harry Herbert) G

- Butcher (Reason) F

- Carpenter (Poulton) G

- Carpenter, gate-maker and builder (Manning) F

- Carrier (Lydiatt) G

- Carrier and school (Adkins) F

- Clockmaker (Ezra Enoch) G

- Cooper (Goffe) F

- Dame school (Priscilla Harris) F

- Doctor (Routh) F

- Doctor (Shelswell) G

- Hurdle maker (Holtom) F

- Plumber and glazier (Fox)

Maker of hydraulic rams G - Post Office G

- Post Office and Drapers G

- Shoemaker (Scruby) F

- Shoemaker (Walton) F

- Sweet shop (Ann Wyatt) G

- Sweet shop (Miss Cook) and Butcher (Fowler) G

- Sweetshop (Fardon) F

- Tailor (Hall) F

- Tailor, bakery and grocer (Lydiatt) G

- Tinker (Hathaway) F

- Vet (Austin) F

- Wheelwright (Hillman & Morgan) F

- Wool merchant and hide curer G

Arnold’s map was based on the following description written in 1937 by his grandfather Joshua Lamb (1856 – 1943), taking a tour along Main Street and describing the village industries that he remembered from his childhood in Sibford Ferris in the 1860s.

Click / touch a highlighted link in the text to fly to the location on the map. Click / touch the pop-up label to return to your position in the text.

The decay of our village industries

Part 2 of Reminiscences of Country Life

A reflection from childhood written later in life in 1937 by Joshua Lamb

The loss to our village of its local industries during the last 70 years is a very serious one. When we were children at least a fourth of the houses were occupied by tradesmen or others who during the greater part of the year were engaged in some local pursuit other than that of agriculture, and it is much to be regretted that influences over which most of them had no control compelled them to relinquish them, or stood in the way of a continuance of them by their successors. This fact, together with the reduction in the number of labourers employed on the farm has been responsible for the destruction, conversion or condemnation of at least 20 cottages in a village whose inhabitants now number 160 exclusive of the large boarding school, and of which number only 10 men are at the present time engaged in the cultivation of the land in addition to the farmers themselves: this is less than one third the number employed in our childhood.

The last house in the village was occupied by a carrier (1) who made the journey to Banbury and back three times a week and did a prosperous business; this was then practically the only means by which wives of farm labourers could ever get into town except on feet, and the journey in the carrier’s cart owing to the bad roads and frequent calls usually took three hours each way; the proprietor was fond of horses, and he had been heard to say that if his father had not followed the hounds he should have done so himself, which rather implied that the “moss” had not grown much under his parent’s feet. The wife kept a little school for any whom their parents cared to send, but as at that time education was only optional regularity of attendance was by no means up to the present standard.

A short distance from the carrier’s residence was the shop of a wheelwright (2) who found constant employment in the building of new farm carts or the repair of old ones, and who could turn his hand also to the manufacture of children’s carriages or anything requiring wooden wheel; we have a vivid recollection of a children’s vehicle made by him which served many purposes in our family at that time.

In addition to work carried on in the above shop by the owner himself was the repair to harness executed by a collarmaker who came over weekly from an adjoining village, and took away with him in addition to a cartload of broken gears to be attended to at home during the coming week, he had by some means lost one of his ears which had completely disappeared.

Next door to the wheelwright lived the local butcher (3) who found frequent calls upon his services in the way of slaughtering pigs and sheep, the former being fed in large numbers in the styes attached to the various residences as well as by the farmers themselves; this man had two brothers residing in the village who were always at ‘daggers drawn’ and the only hand to hand fight we ever witnessed between these, and as a result of a later quarrel the home of one brother was fired by the other, fortunately without any serious consequences. The only son of the aforementioned butcher ultimately became Mayor of one of the largest London boroughs.

Nearby was an old barber (4) who was very fond of tobacco if not of drink, and the rank smell of his breath when he blew loose hairs from one’s neck after the ‘operation’ is not likely soon to be forgotten. He visited the villages around in pursuit of his calling, and supplemented his small income by selling watercress when in season which he obtained in one of the local ponds. During washing operations in her early married life his wife lost her wedding ring, and it was not until twenty years afterwards that her husband dug it up on his allotment nearly a mile away, where it had evidently been taken among house refuse.

Within a few doors of the hairdresser, we find a cooper (5) at work mending and repairing wooden tubs and barrels which were in those day more in request than the present time; it was usual then for many households to make their own beer and cider, and the number of wooden vessels required for these purposes in addition to barrels in which the products were ultimately stored was very considerable.

A tinkering blacksmith (6) resided in the adjoining house to whom all our leaking buckets and cans were taken to be soldered, he was indeed a Jack of all Trades, and it was very few broken things he could not mend, and when not otherwise employed he would make horse shoes for his blacksmith brother at the other end of the village.

From the tinker to the baker (7) was only a few steps, and we used to love to see the latter stuff his great oven full of faggots, and afterwards rake out most of the burnt material before putting in the batch of bread. This collected all the remaining cinders and ashes, and they were ultimately found firmly fixed into the bottom of the loaves; this old bakehouse used to swarm with crickets which kept up a lively chirruping both day and night. The room over the large oven was generally occupied by some damp corn or other market produce sent to be dried by a local farmer. This baker had a notoriously bad name in the village, and after his death even the grave at first refused to receive him, for it coped in immediately his coffin was placed by its side.

At the back of the baker’s shop dwelt a man who was a little above the ordinary labouring class, and who earned a precarious livelihood at land surveying, bookkeeping, etc (8), and in connection with the latter was credited either rightly or wrongly with having more or less tampered with the work entrusted to him: he was almost the first scholar to enter the large boarding school, having, it is said, raced another through the village for the honour. He was not a favourite with the village boys in his later life among whom he was known as ‘Whiskery Will’, and during a misunderstanding with them a large stone was dropped over a wall which unfortunately fell on his head and resulted in considerable trouble to the lad who was responsible for this exploit.

Our village was also honoured by the presence of a Veterinary Surgeon (9) who was also known locally as the ‘Quack Doctor’. His potations for our ailing animals generally resulted either in a kill or cure. His practice was by no means a large one, and he had for a housekeeper a slovenly old jade who spent every available halfpenny in drink, and one morning the ‘grandfather’ clock came to be examined because it had stopped in the night. It was found that the works were missing having been pawned to provide her with an additional supply of her favourite beverage.

We come next to a busy carpenter’s shop (10) where all local gates etc., were made, repairs executed and building operations undertaken. This house had been burnt down a short time before when one of the sons was struck while in bed by the lightning which caused the fire, the results being rather serious.

But we must not forget Old Shuckey (11) the way to whose little shop lay along a garden path at the end of which was a double door with a heavy knocker attached, which for the convenience of the children who were her best customers, was placed where it could be reached on the lower half; a vigorous use of this would generally result in the top half of the door being opened, and a gentle enquiry being made as to what was wanted, and whether it happened to be a pound of candles or a box of percussion caps the order was soon executed and the double doors again closed and bolted. On another occasion it might me that a couple of ounces of raisins was required, in which event it was probable that one would have to bitten in two to ensure that the customer had no more or less than the stipulated amount. Here too could be purchased a cure for all children’s ailments, a supply being always in hand of Senna leaves, Chamomile flowers, Brimstone or Glauber’s Salts, and on one occasion a little girl was overheard repeating again and again as she ran to the shop, “A little bit of pitch to make Aunt Sarah some pills.”

Another little school (12) which was kept for middle class children by a spinster of doubtful age was conducted in a cottage opposite to where our doctor (13) resided. And when the time came that her marriage was to take place to the baker previously referred to, who had himself proffered his hand and had been nearly accepted, made arrangements with the driver of a traction engine to draw up immediately under the flag which hung across the road opposite the house and thoroughly smoke it while the marriage celebrations were proceeding.

At the back of this house stood a row of old cottages which were afterwards pulled down, and during the demolition of one of them bushels of old egg shells were found at the back of the chimney. These were tucked tightly into one another, showing that at least a dozen had been used at a time. There were a good many whisperings about the village as to how the recent occupier of that particular cottage had come into possession of them but he himself kept a discreet silence.

Now we cross the road to the shoemaker’s shop (14), the occupier of which was a crusty old man with a wife of similar disposition, and whenever children were sent there with shoes to be repaired, they left as speedily as possible and deferred calling again for the finished goods until the last possible moment. But they did not get on better with his next door neighbour who occupied about 2 acres of orchard land on which he kept a cow, except when she died, as she appeared to do pretty often, at which times the hat would be sent round and a goodly sum collected towards another start; the village boys called him ’Bummock’, for what reason was not known, but it made him mad with rage, and his wife would come out and assist him in his deprecations of all and sundry.

Almost before we were up in the mornings we frequently heard the cry in the street, “Herrings were all alive”, and this rather remarkable but doubtless correct statement came from a blind man who was being led round the village by a little girl; he was a most energetic person who was able by dint of perseverance to provide an honest living for himself and family by making baskets and dealing in fish, fruit etc., for some unexplained reason all his five children with the exception of the little girl were born idiots, one of whom lived to middle age. His sight was lost when as a boy he was leaning over his brother’s shoulder watching him trim a rose tree when the knife slipped and entered his eye, losing him the other as a result of it.

Now we come to another shoemaker (15) who like the one previously referred to was a terror to the boys who gave him a wide berth whenever possible. Why these two old shoemakers should have such an aversion to those who were their best customers we are unable to say.

A maltster and beerhouse keeper (16) came next; the malting premises were burnt down in our childhood and in after years the beer licence was forfeited after an unsuccessful attempt on his part to obtain a full one for the premises. his was opposed by the villagers who during the remaining few years of his life were not allowed to forget the injury he said they had done him.

Only three cottages separated the beerhouse from the village tailor (17) who sat at his board from morning till night making new garments or repairing old ones for the local residents; there was something about the smell of the tailor’s shop which is unforgettable: probably it had something to do with corduroy cloth which was always much in evidence.

The ring of the hammer in the blacksmith’s shop (18) nearby was distinctly heard all day through the tailor’s window, and a great business was done there in the way of shoeing horses, and general farm repairs. The bills issued half yearly were of great length and toted up to a considerable sum. This was the trysting place for the youth of the village in the winter evenings when the glow of the fire and the ring of the anvil were much enjoyed.

At the top of the village lived the ‘Crow Butcher’ or ‘Hedge Carpenter (19)’ as he was often called, the former referring to his being frequently required to kill and dress ailing animals, many of which he would then purchase and retail for what he could make, and the latter to his handiness in putting up post and rails, and doing other carpentering on the farms.

The miller too at that time was a busy man who employed two assistants fetching corn and delivering goods. Both mills were kept constantly working whenever possible, and several villages were supplied from that one source with meal for their stock as well as to some extent with refined flour for breadmaking, but now very little done at all in this way. The miller’s cart is never seen on the roads and the mill pounds are choked with mud.

We still have a doctor, we are glad to say, and a little shop supplies article of food, but the blacksmith has practically nothing to do and most of the other industries appear to have gone for ever.

You may also like to read Joshua’s Part 1 of Reminiscences of Country Life, full of insights into life in the Sibfords between 1867 and 1937.