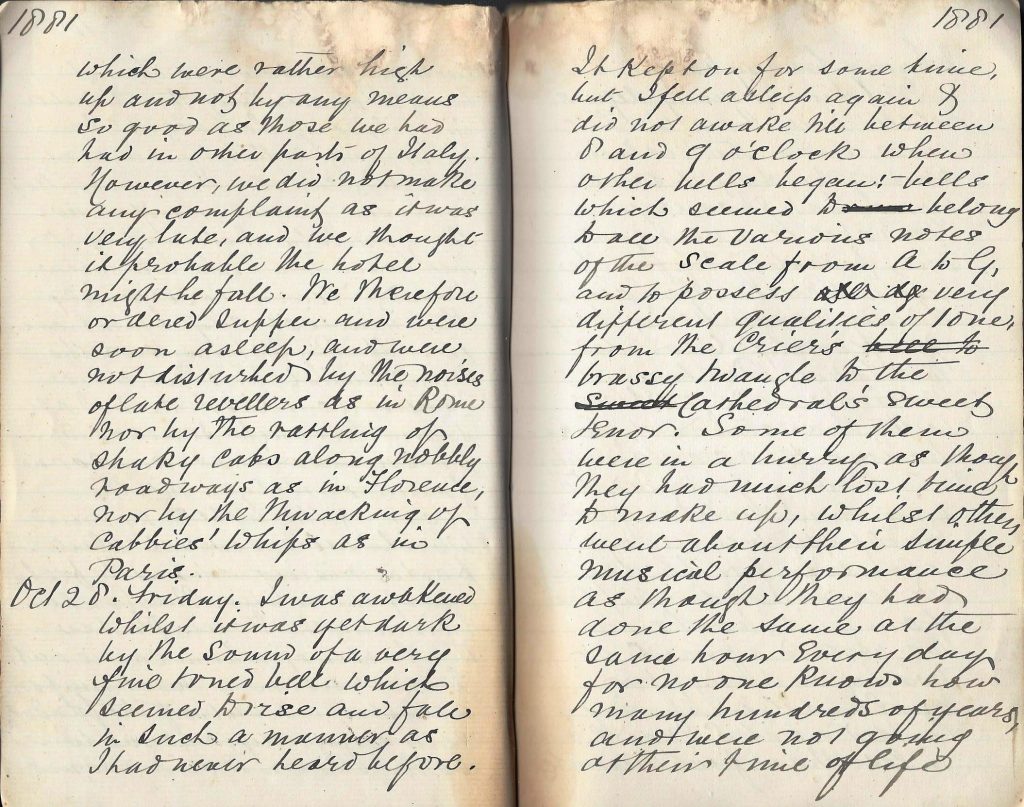

Stevens 1881-10-28

I was awakened whilst it was yet dark by the sound of a very fine toned bell which seemed to rise and fall in such a manner as I had never heard before. It kept on for some time, but I fell asleep again and did not awake till between 8 and 9 o’clock when other bells began:- bells which seemed to belong to all the various notes of the scale from A to G, and to possess very different qualities of tone, from the crier’s brassy twangle to the cathedral’s sweet tenor. Some of them were in a hurry as though they had much lost time to make up, whilst others went about their simple musical performance as though they had done the same at the same hour every day for no one knows how many hundreds of years, and were not going at their time of life to hurry for anybody.

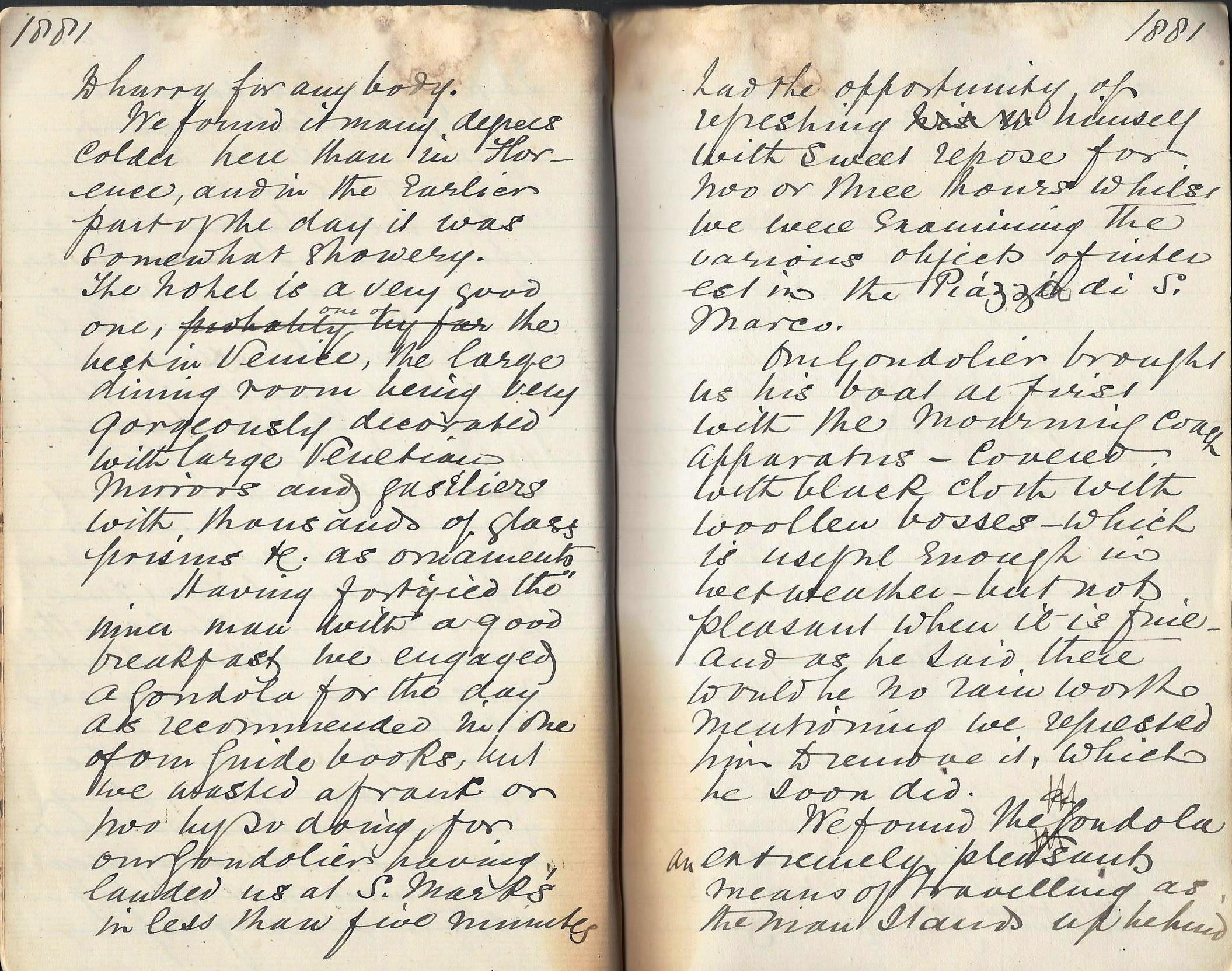

We found it many degrees colder here than in Florence, and in the earlier part of the day it was somewhat showery. The hotel is a very good one, one of the best in Venice, the large dining room being very gorgeously decorated with large Venetian mirrors and gaseliers with thousands of glass prisms etc as ornaments.

Having fortified the inner man with a good breakfast, we engaged a gondola for the day as recommended in one of our guide books, but we wasted a franc or two by so doing, for our gondolier having landed us at S. Mark’s in less than five minutes had the opportunity of refreshing himself with sweet repose for two or three hours whilst we were examining the various objects of interest in the Piazza di San Marco.

Our gondolier brought us his boat at first with the mourning coach apparatus – covered with black cloth with woollen bosses – which is useful enough in wet weather – but not pleasant when it is fine – and as he said there would be no rain worth mentioning we requested him to remove it, which he soon did.

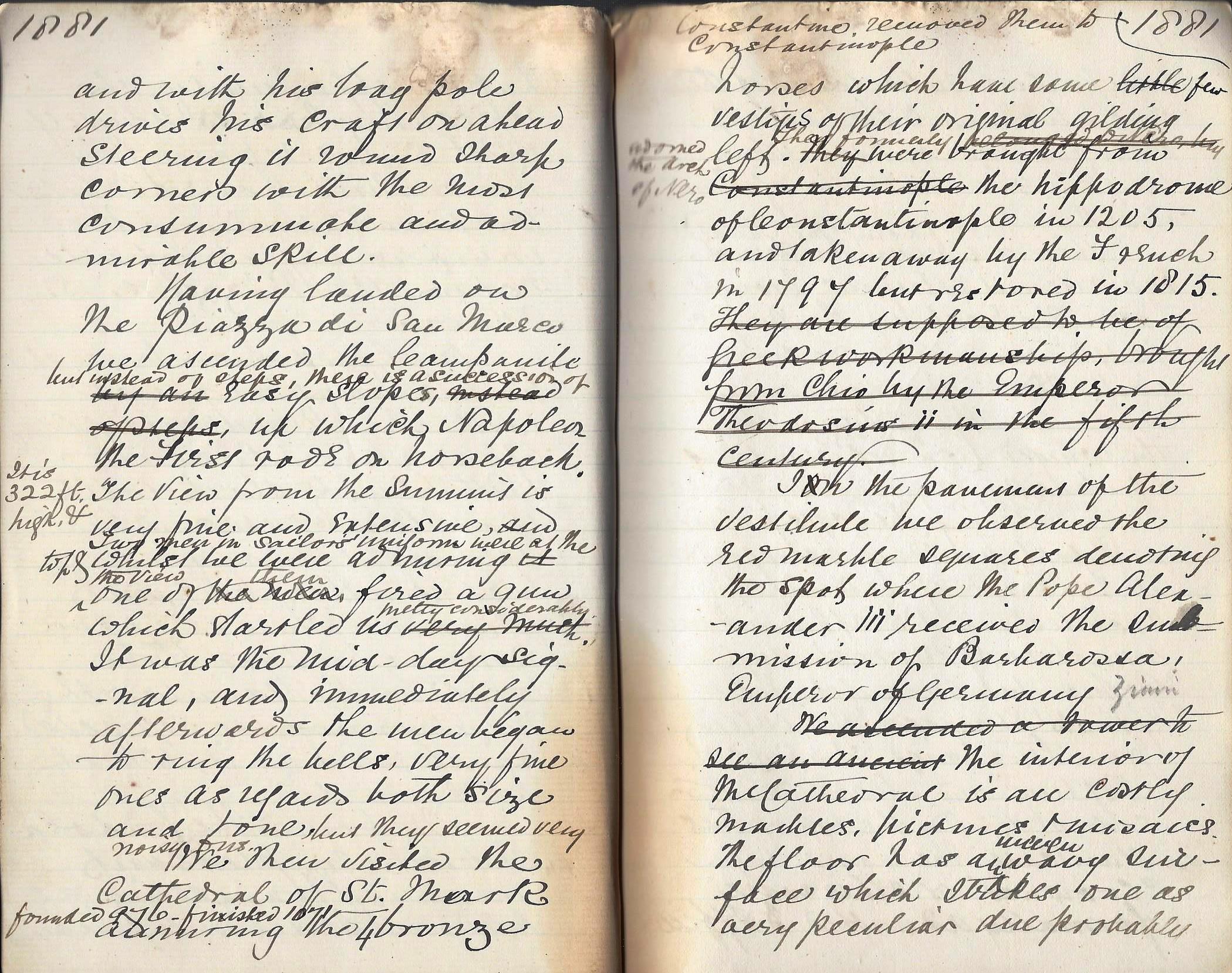

We found the gondola an extremely pleasant means of travelling as the man stands up behind and with his long pole drives his craft on ahead steering it round sharp corners with the most consummate and admirable skill.

Having landed on the Piazza di San Marco we ascended the Campanile but instead of steps, there is a succession of easy slopes, up which Napoleon the First rode on horseback. It is 322 feet high and the view from the summit is very fine and extensive. Two men in sailor’s uniform were at the top and whilst we were admiring the view one of them fired a gun which startled us pretty considerably. It was the mid-day signal, and immediately afterwards the men began to ring the bells, very fine ones as regards both size and tone, but they seemed very noisy to us.

We then visited the Cathedral of St Mark founded 976 – finished 1071 – admiring the 4 bronze horses which have some few vestiges of their original gilding left. Constantine removed them to Constantinople. They formerly adorned the arch of Nero, were brought from the hippodrome of Constantinople in 1205, and taken away by the French in 1797 but restored in 1815.

In the pavement of the vestibule we observed the red marble squares denoting the spot where the Pope Alexander iii received the submission of Barbarossa, Emperor of Germany.

The interior of the Cathedral is all costly marbles, pictures and mosaics. The floor has an uneven wavy surface which strikes one as very peculiar due probably to the partial subsidence of the soil. We went to the back of the high altar and saw what purports to be the tomb of Saint Mark.

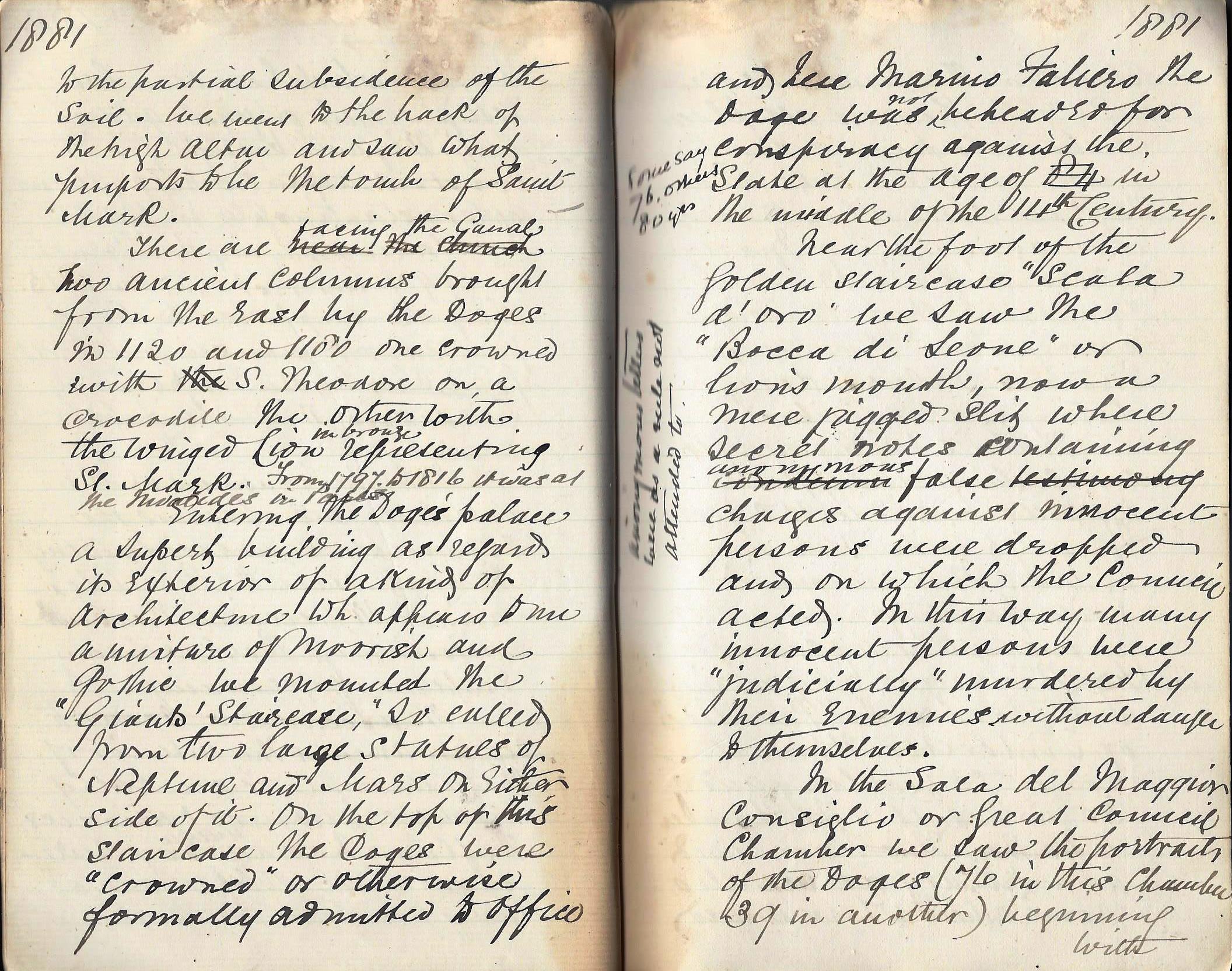

There are facing the canal two ancient columns brought from the east by the Doges in 1120 and 1180 one crowned with S. Theodore on a crocodile the other with the winged lion in bronze representing St Mark. From 1797 to 1816 it was at the Invalides in Paris.

Entering the Doges’ palace a superb building as regards its exterior of a kind of architecture which appears to me a mixture of Moorish and Gothic we mounted the “Giants’ Staircase,” so called from two large statues of Neptune and Mars on either side of it. On the top of this staircase the Doges were “crowned” or otherwise formally admitted to office and here Marino Faliero the Doge was (not) beheaded for conspiracy against the state at the age of 84 (some say 76, others 80 years) in the middle of the 14th century.

Near the foot of the golden staircase “Scala d’oro” we saw the “Bocca di Leone” or lion’s mouth, now a mere ragged slit where secret notes containing anonymous false charges against innocent persons were dropped and on which the council acted. (Anonymous letters were as a rule not attended to.) In this way many innocent persons were “judicially” murdered by their enemies without danger to themselves.

In the Sala del Maggior Consiglio or Great Council Chamber we saw the portraits of the Doges (76 in this chamber, 39 in another) beginning with Obelerio the ninth Doge in 804. They are all placed in chronological order and are of uniform size, but the place which should have been occupied by Marino Faliero is painted black and contains the following inscription “Hic est locus Marini Falieri decapitati pro criminibus”

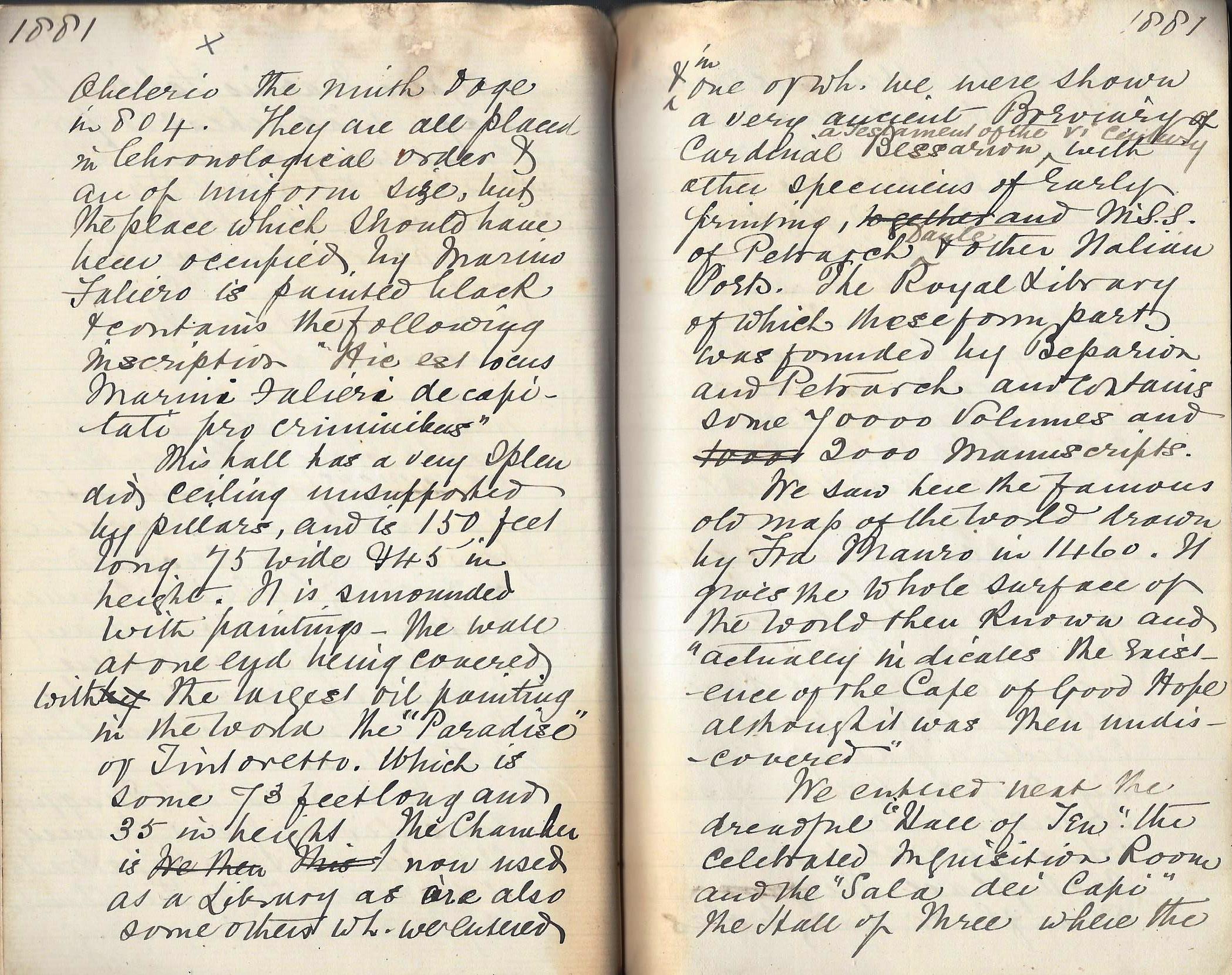

This hall has a very splendid ceiling unsupported by pillars, and is 150 feet long, 75 wide and 45 in height. It is surrounded with paintings – the wall at one end being covered with the largest oil painting in the world the “Paradise” of Tintoretto. Which is some 73 feet long and 35 in height. The chamber is now used as a library as are also some others which we entered and in one of which we were shown a very ancient Breviary of Cardinal Bessarion, a testament of the vi century, with other specimens of early printing, and manuscripts of Petrarch, Dante and other Italian poets. The Royal Library of which these form part was founded by Bessarion and Petrarch and contains some 70000 volumes and 2000 manuscripts.

We saw here the famous old map of the world drawn by Fra Mauro in 1460. It gives the whole surface of the world then known and “actually indicates the existence of the Cape of Good Hope although it was then undiscovered”.

We entered next the dreadful “Hall of Ten”, the celebrated Inquisition Room and the “Sala dei Capi” the Hall of Three where the last possible appeal was made.

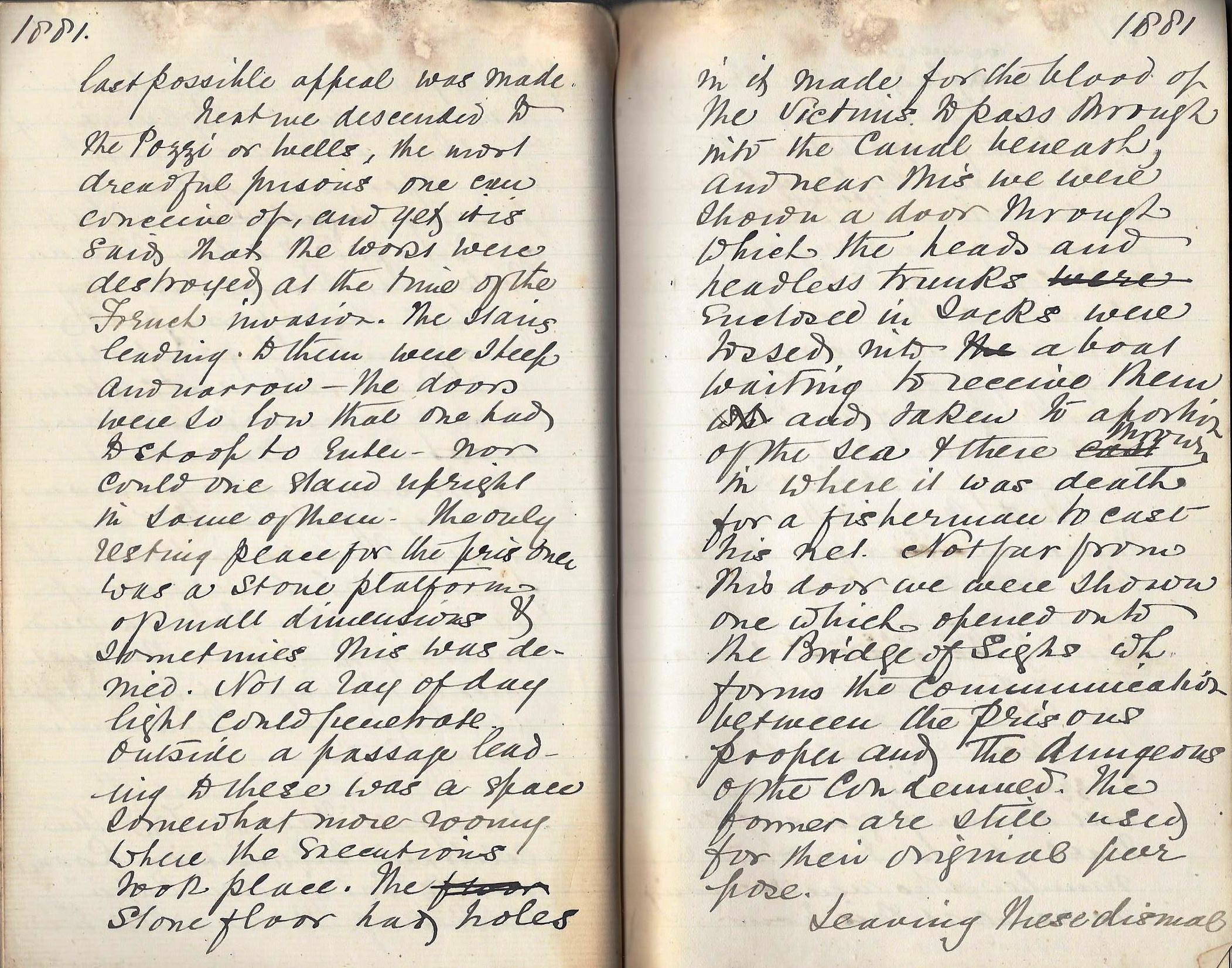

Next we descended to the Pozzi or Wells, the most dreadful prisons one can conceive of, and yet it is said that the worst were destroyed at the time of the French invasion. The stairs leading to them were steep and narrow – the doors were so low that one had to stoop to enter – nor could one stand upright in some of them. The only resting place for the prisoner was a stone platform of small dimensions and sometimes this was denied. Not a ray of daylight could penetrate. Outside a passage leading to these was a space somewhat more roomy where the executions took place. The stone floor had holes in it made for the blood of the victims to pass through into the canal beneath, and near this we were shown a door through which the heads and headless trunks enclosed in sacks were tossed into a boat waiting to receive them and taken to a portion of the sea and there thrown in where it was death for a fisherman to cast his net. Not far from this door we were shown one which opened onto the Bridge of Sighs which forms the communication between the prisons proper and the dungeons of the condemned. The former are still used for their original purpose.

Leaving these dismal dens we were glad to see the blessed light of day again.

On the piazza between the Cathedral and the Doges’ Palace are two columns of apparently Eastern origin and very ancient, with coptic and hieroglyphic characters. They were brought from Acre, as was also the porphyry group on the angle near the gate of the Ducal Palace, whose subject is a matter of controversy.

In the Natural History Museum is a fair collection, the most noticeable being models in wax representing various steps in the formation of the human being and of a chicken in the egg.

Descending into the piazza again, we saw the well known pigeons of St Mark, some hundreds in number who were receiving as usual at this hour the admiration and the gifts of the public. These birds are fed at the public expense, but gratefully and cheerfully receive the smallest contributions at other times.

We ascended a light iron staircase adjoining a watchmaker’s shop to see a famous old clock, which on certain festivals exhibits a moving set of of figures of the Virgin Mary, Joseph etc and tells at all times the day of the month and of the week, the hour and the minutes in Arabic numerals, thus 12:5 for 5 minutes past 12, and is illuminated at night.

The Arcade round the piazza is very handsome and the shops under it are the best in Venice. At night time the place is extremely well lighted and being almost crowded with Venetians who come here to stretch their legs, which they can scarcely do anywhere else in the city, presents a gay and lively scene.

We found our gondola and gondolier where we had left them and taking our seats committed ourselves to his guidance.

He took us first to a Church opposite the “Grand Hotel” where we were living, called Santa Maria della Salute. It was built 1631 – 1682 in fulfilment of a vow of the Venetians on the cessation of the plague (1630) which destroyed 44000 people in Venice. It has a fine dome and is rich in paintings and statues. 200,000 piles were used in forming its foundation. Then, turning in the cleverest way imaginable the corners of narrow canals and passing other gondolas large and small where there seemed to be not half room enough and yet without the slightest collision, he landed us at the Church of Santa Maria dei Frari, the Westminster Abbey of Venice. It is a vast and magnificent church, built in 1250, and contains the tomb of Titian who died during the plague in 1573 (born in 1477) and that of Canova. The latter was designed by the sculptor for Titian’s tomb, but as he died before it was erected, it was devoted to himself, whilst another was designed for Titian. They are both very large, built of white marble against the N and S walls of the nave. Titian being buried on the North side and Canova on the South. There are numerous other tombs of eminent persons and many paintings.

We passed the Armenian College where Lord Byron spent a considerable time studying the Armenian language and antiquities of Venice. A corner house having a statue of a Moor in one of the gables angles was pointed out as that of “Othello, the Moor of Venice”.

The next church we visited was that of the “Redentore” or Redeemer – a beautiful structure. It is said to be Palladio’s best work. A barefooted Capuchin showed us over the building which contains a great number of fine paintings and sculptures. It was founded in 1575 by the Republic of Venice as a thank offering for deliverance from the plague which was very destructive in that year. The carved white marble altar is especially fine.

We visited some other churches and then returned to our hotel to dinner. The weather was somewhat milder than it was last evening. I went par terre to the Piazza of St Mark which I found very lively with a band of musicians in the centre making things merry and a great number of persons walking about. Returning through the narrow courts (they are not worth the name of street) to the hotel I watched the gondolas passing and repassing on the Grand Canal, and calculated that the water moved at the rate of not more than a quarter of a mile an hour.

28 Oct 1881

28 Oct 1881

28 Oct 1881

28 Oct 1881

28 Oct 1881

28 Oct 1881

28 Oct 1881

28 Oct 1881